A few weeks ago, I wrote about the research on social media and teen mental health—which is, you know, kind of my thing. I figured I was done writing about it for awhile.

But you know how athletes often announce their retirements and then change their minds? Like Tom Brady in 2021? Or Michael Jordan in 1995 (and 2001)?

There are a few (minor) differences between those guys and me. Most notably, I did not come out of retirement to help the Looney Tunes win a basketball game against aliens who’ve infiltrated the bodies of NBA stars.

What we have in common, though, is this: we weren’t ready to step away just yet.

So, I’m back this week with more thoughts on the issue of teen social media use and mental health. For the last time. At least for a while. Maybe.

Let’s embrace the uncertainty

The current debate has been mostly centered on the following question:

Has the introduction of social media in the past 10-15 years caused the increase in prevalence of mental health problems in teens?

At this point, most of what I’m reading and hearing is a resounding yes (especially for girls).

I don’t necessarily disagree with this. Just to level set: I think there is a very good chance (my current number is probably around 75%) that social media has contributed to the teen mental health crisis. At the same time, I think large-scale mental health crises are complex phenomena, that there are likely multiple causes, and that we need to make sure we’re approaching the data with the scrutiny it deserves. It’s this nuance that, I think, has been missing from the conversation.

We need to make sure we’re not missing anything, even if it means the story is not as simple, or satisfying, or certain as we’d like it to be. So, let’s embrace the uncertainty and talk about what we know and what we don’t know on this issue.

Note: psychologist Jonathan Haidt and his team have created a number of incredibly helpful resources on this topic. I’ve used these extensively both in writing this post, and in my work more generally. These resources include two collaborative review documents (Adolescent mood disorders since 2010 and Social media and mental health) and charts tracking CDC suicide statistics and gender differences in mental illness prevalence rates.

The case that has (mostly) convinced me

Here is the basic argument, and data, that supports the idea that social media has caused the mental health crisis. I’ll try to keep this brief, because others have written on this extensively (e.g., see Jonathan Haidt’s recent Substack post).

Mental health concerns and social media use have increased in tandem. Mental health concerns, including depression, anxiety, and suicide have increased in prevalence, especially among girls, in recent years. This certainly seems to be true in the U.S. and U.K, where most of this research has taken place, but there are also some signs that this is happening in other countries (though not all). In many datasets, the increase seems to be particularly profound starting in about 2012. You know what else started in 2012? You guessed it. Social media became widely available on smartphones, and teens started using it a lot.

We have the beginnings of causal evidence. We have many, many studies that do a version of the following: ask teens how much they’re using social media, and look at associations between that number and their mental health. A related, though more rigorous, version of these studies are randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that randomly assign some individuals (mostly adults; very few of these RCTs involve teens) not to use social media for a certain period of time, and then see how it impacts their well-being.

These studies are good for answering a specific, individual-level question: in our current world, does using more or less (or no) social media have an impact on our mental health? I wrote about this a few weeks ago. But this is a different question than the population-level question we’re addressing here: has the introduction of social media *in general* contributed to rising rates of mental health concerns? Of course, these studies inform the answer to the population-level question, but they don’t answer it.

There is one 2022 study, though, that I’ve found particularly convincing that does directly address the population-level question. It is quasi-experimental, meaning the researchers use circumstances that naturally occur in the world to mimic an experimental design. The researchers use the fact that Facebook was introduced at different times at different colleges to see how the introduction of Facebook on a given campus changed rates of mental health concerns. They find that after Facebook showed up, rates of mental health concerns (especially depression) increased.

There are other quasi-experimental studies out there (e.g., this and this) that similarly look at the introduction of high-speed Internet, and find associations with poorer mental health. These also provide some causal evidence (though, they do not address social media specifically).

We have common sense, too. There is also, of course, the common sense argument. This is risky, as I stated above, because common sense in the absence of research has also led us to do things like blood letting and, much more recently, routine episiotomies.

And yet, the common sense argument has been the foundation of much of what drives our conclusions here. We know that things like in-person social interaction and being outside are important for teens’ mental health. To the extent that social media gets in the way of that, this is an issue.

Further, many other explanations for possible increases in mental health concerns—exposure to negative news and current events (wars, gun violence, climate change), increasing academic and social pressures, unhelpful narratives around mental health—are likely fostered by and intertwined with social media, so in many cases, social media may still be an amplifier (even if not a direct cause).

As I said, taken together, this data has ultimately led me to conclude that it is likely that social media has contributed to the mental health crisis.

But now I want to get into the uncertain part. Because I think that’s important, too.

Things that make me feel less certain

A centerpiece of the argument that social media is causing the mental health crisis is the idea that mental health symptoms have skyrocketed since 2012, and they have increased faster in teens (versus adults) and girls (versus boys).

The 2012 inflection point is used as evidence for social media being the cause (i.e., why else would we be seeing a sudden, rapid increase at that point?). The gender difference—accompanied by the assumption that social media is worse for girls—is used to rule out alternative explanations (i.e., it can’t be caused by the financial crisis, for example, because why would that be worse for young girls?)

On average, it does seem like rates of mental health concerns have increased since 2012, and more so for girls than boys. But a few facts make me uneasy about this nice, clean narrative.

Symptoms vs. diagnoses. Many of the datasets we’re talking about do not actually assess rates of mental illness. The widely-discussed CDC data that came out a few weeks ago, for example, asks high school students questions like: “During the past 12 months, did you ever feel so sad or hopeless almost every day for two weeks or more in a row that you stopped doing some usual activities?” Students who answer “yes” to this question would certainly be more likely to be diagnosed with depression, but this is not, in itself, a measure of diagnosed depression.

Self-report measures. Relatedly, most of the datasets we’re discussing (e.g., NSDUH, YRBS) involve self-report measures of mental health symptoms. Though this likely would not entirely explain the large increase we’ve seen in recent years, self-report measures are certainly subject to over-reporting (and overinterpretation, as we discussed recently), especially when teens themselves are frequently bombarded with headlines about the teen mental health crisis.

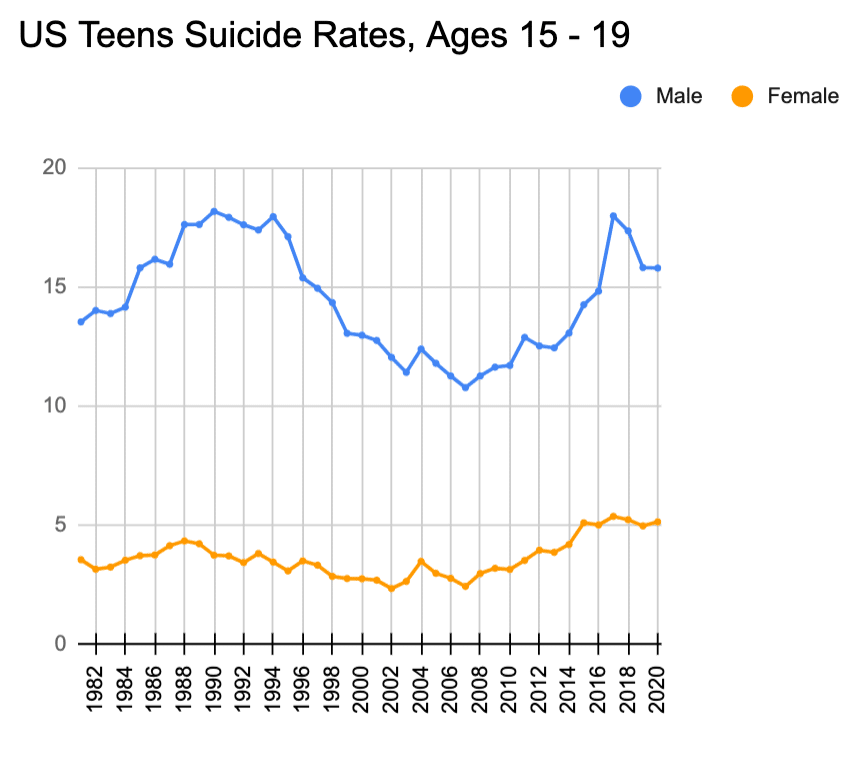

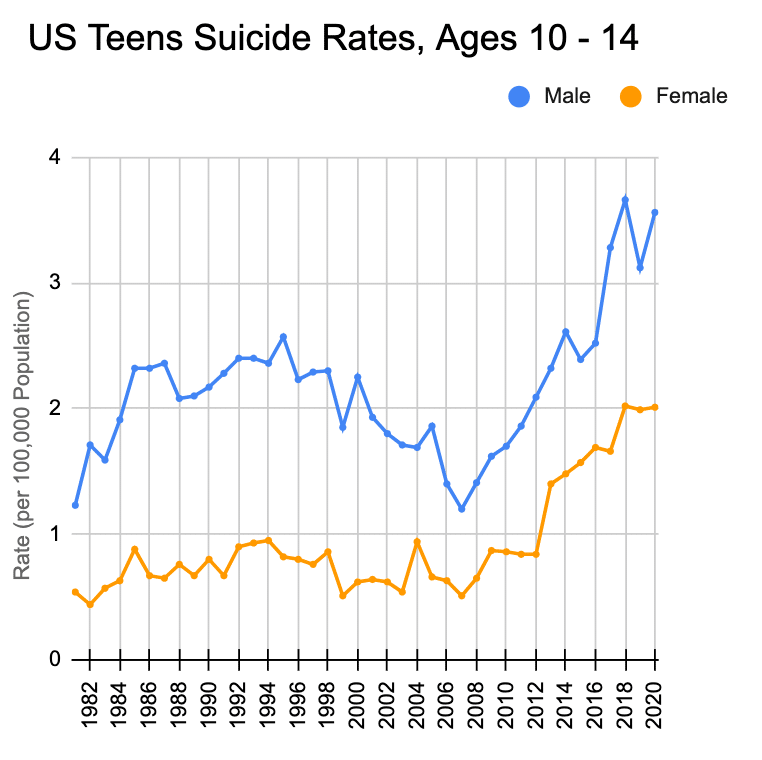

Suicide rates. One way around the issues of self-report is to look at rates of suicide. To be clear: suicide is a tragedy, and even one suicide by a young person is too many. This makes it especially important that we understand the numbers and convey them accurately. The CDC collects data on suicides (as well as other causes of mortality) in the U.S. every two years. They separate it out by age and gender, including ages 10-14 and 15-19. A few things here give me pause:

- For 15- to 19-year-olds, rates for boys were actually higher in the late 80s/early 90s than they are now. There is little consensus on why this would be the case.

- We are talking about extremely small numbers, and anytime you’re talking about small numbers, interpreting “percentage change” is tricky. Among girls ages 10-14, there was less than 1 suicide (0.84) per 100,000 in 2012. In 2020, there were about 2 suicides (2.01) per 100,000. So, the rate has more than doubled (a 139% increase). For boys, it went from 2.09 to 3.56 (a 70% increase). But is the difference between these two meaningful? Or is it just that the rate among girls started out particularly low?

- There have been other times in the past few decades when rates increased, too (albeit, less so than in recent years). But I think this reflects part of the issue with drawing conclusions from such small numbers. Among girls ages 10-14, for example, the suicide rate more than doubled (a 104% increase) between 1982 (0.44 per 100,000) and 1992 (0.9 per 100,000).

Suicide rates have increased among nearly all age groups (not just teens) and remain higher in adults than in teens. They have certainly increased more among adolescents (especially ages 10-14), though it is worth noting that this younger age group started out with much lower rates overall.

Gender differences in rates of symptoms. When we look at the major datasets being used to assess rates of mental health concerns in the U.S. and U.K., the gender difference story is a bit murky. In many cases, rates among girls have gone up more quickly than boys, but in some cases, there’s no difference, or rates among boys have increased more than girls (e.g., rates of depression among UK 13- to 19-year-olds).

Gender differences in social media effects. It is not clear from the research that social media is actually worse for girls than boys. There’s certainly some evidence pointing in this direction, and it makes intuitive sense, given, for example, that girls are more likely to struggle with body image and appearance concerns (and social media offers plenty of fodder for that).

But some studies find no difference by gender, and there is simply not a scientific consensus on this yet. Further, it’s not clear to me why many of the mechanisms we would expect to drive the relationship between social media use and mental health (e.g., interference with in-person activities, sleep disruption, exposure to problematic content) would necessarily differ by gender.

We need to be careful about the “teen girls are in crisis” narrative—both because boys are struggling, too, and because the research on gender differences is still emerging. I’m seeing a lot of commentary about girls falling apart in the face of their screens, about their fragile self-esteem in a world of constant selfies, etc. Let’s make sure our (gendered) assumptions about what girls can and cannot handle aren’t coming before the data.

Other possible explanations. Finally, we come to perhaps the biggest question of them all: what other explanations, besides social media, could there be for rising rates of mental health concerns in teens?

There are likely multiple causes of the mental health crisis. Social media certainly may be one of them, but it’s unlikely to be the only one. We like simple explanations. We want to be able to discover a single cause and say aha! That was it! But this is not how the world works. Explanations for why large-scale phenomena occur are, by necessity, complex.

Similarly, we all suffer from what’s called the availability heuristic. When we make decisions, we’re biased toward relying on information that comes to mind more quickly and easily.

So, when we think of teens and how they’ve changed in the past 10 years, what’s the thing that comes most easily to mind? Social media. We need to be careful not to discount other factors, just because they don’t fit our easily accessible mental models.

A few alternative explanations that have been proposed include: the global financial crisis, rising income inequality, wars, school shootings, racial inequality, climate change, the opioid epidemic. Some of these potential causes have been explained away by timing—e.g., how could a financial crisis in 2008 impact teens in, say, 2016? Well, that’s the thing about population-level phenomena. They have downstream effects that are hard to measure and predict.

Kids’ mental health is also, unsurprisingly, strongly affected by the health and circumstances of their parents. Having a parent who is (or was), for example, struggling with opioid abuse has far-reaching impacts. Some of these explanations seem more plausible than others to me, but the truth is that we don’t know—we’ve been so focused on social media as the explanation that we haven’t given other possibilities the research attention they deserve.

Where do we go from here?

Ultimately, my worry in embracing social media as the (single, definitive) cause of the mental health crisis is that we’ll forget about the many other factors that are so crucial to supporting teens’ mental health. We’ll forget about addressing the challenges brought on by all those other potential causes of the crisis. Changing the way teens use (or don’t use) social media certainly may make a difference for their mental health, but if we’re pinning our hopes for fixing this crisis entirely on social media, we’re going to be disappointed.

Will we ever have enough evidence to be absolutely, 100% certain that social media is a cause of the teen mental health crisis? Probably not. We’ll get more and better evidence over time, yes, but our information will always be imperfect.

The question is quickly becoming: how certain do we need to be to act? If there’s some evidence of harm, maybe that’s enough to necessitate change. Even if we’re still uncertain.

A fact that you absolutely do not need to know about me is that I was obsessed with Michael Jordan during elementary school. For the entirely of my third grade year, I wore a Bulls Jordan jersey to school minimum once a week. Incidentally, I was not good at basketball.

Bet you did not have “Space Jam reference” on your Techno Sapiens Monday bingo card. I loved this movie when I was younger (likely related to the aforementioned Michael Jordan fandom). Have not seen it recently, but very curious if it holds up. Based on this IMDB synopsis, I think it just might! Swackhammer, owner of the amusement park planet Moron Mountain is desperate to get new attractions and he decides that the Looney Tune characters would be perfect. He sends his diminutive underlings to get them to him…the Nerdlucks turn the tables and steal the talents of leading professional basketball stars to become massive basketball bruisers known as the Monstars. In desperation, Bugs Bunny calls on the aid of Michael Jordan, the Babe Ruth of basketball, to help them have a chance at winning their freedom. [Also, no, I have not seen the 2021 reboot. How dare you even ask.]

I’ve been slightly hesitant to jump into this debate because I’m finding it increasingly difficult not to get involuntarily relegated to a “camp.” Expressing any doubts about the evidence that social media is the sole and definitive cause of the mental health crisis, or conversely, expressing support for the idea that social media is a contributing factor, seems to immediately place me on one side or the other. I do not want to be in a camp. I’m not a camp person. Too many mosquitoes and cult-y group chants. Plus, living on one side of a debate is dangerous. It can make it hard to change your opinion, to integrate new evidence when it becomes available, to backtrack on something you said previously because you don’t want to look like a big, old dummy. I’ve tried my best here to stay out of any camps, and just present what I think we know and don’t know.

Of no consequence, I will just mention that most of the other writing I’ve seen on this topic has been written by men, and I’ve seen exactly zero references to episiotomies in said writing. Just sayin’.

Another example of the availability heuristic: we overestimate our chances of dying in a plane crash (versus, say, a car accident). Car accidents are far more common, but it’s easier for us to call to mind vivid images and scary news headlines about plane crashes. At any signs of turbulence, I also happen to call to mind vivid images of a flight I once took from North Carolina to New York. The turbulence was so bad that, at one point, half the overhead bins spontaneously popped open, people were silently crossing themselves, a food cart toppled over and spilled coffee everywhere, and a flight attendant tumbled—I’m talking multiple somersaults—down the aisle. It’s a miracle I ever got on a plane again.

Keep Reading

Want more? Here are some other blog posts you might be interested in.